In today’s climate of heated rhetoric and real threats of political violence, a 400-year-old play put on for free in New York City has become the latest source of controversy. At the opening of Act 3, a Donald Trump-like character is stabbed to death by a group of ambitious senators in the latest production of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar.

For a number of critics, the suggestion of Trump’s assassination on stage went too far, especially in today’s volatile political climate. The play opened on June 12 as part of the New York City Shakespeare in the Park series and immediately prompted a firestorm between the play’s critics and defenders.

The president’s son, Donald Trump Jr., denounced the performance over Twitter, questioning whether the performance was art or constituted threatening “political speech.”

After Republican members of Congress were targeted in a mass shooting on Wednesday, Trump Jr. pointed to political commentary by Harlan Z. Hill saying, “Events like today are EXACTLY why we took issue with NY elites glorifying the assassination of our President.”

Sponsors of The Public Theater, the group putting on the production, began withdrawing their support. Delta Airlines and and Bank of America issued statements on Sunday announcing they were pulling financial support for the production of Julius Caesar.

“Their artistic and creative direction crossed the line on the standards of good taste,” Delta said in it’s statement.

Bank of America announced their withdrawal of support for the production in a tweet saying, “The Public Theater chose to present Julius Caesar in such a way that was intended to provoke and offend. Had this intention been made known to us, we would have decided not to sponsor it.”

After Trump, Jr.’s first tweet questioning whether taxpayer money had gone toward the free Shakespeare performance, the publicly funded National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) put out a statement saying definitively that “no NEA funds have been awarded to support this summer’s Shakespeare in the Park production of Julius Caesar,” and no funds supporting The Public Theater or its parent company.

So did the theater company go too far in casting Trump as the ill-fated Julius Caesar?

Oskar Eustis, creative director of The Public Theater and director of this year’s Julius Caesar, said absolutely not.

The production in no way advocates for political violence, but does quite the opposite, he told the audience on opening night.

“Those who attempt to defend democracy by undemocratic means pay a terrible price and destroy the very thing they are fighting to save,” he said.

Reciting one of the many themes of the play, he warned of political leaders and the public being manipulated to “destroy the very institutions that are there to serve and protect them.”

None of the lines of Shakespeare’s original were changed, though Caesar’s wife Calpurnia speaks with a Slavic accent. But the play is whole.

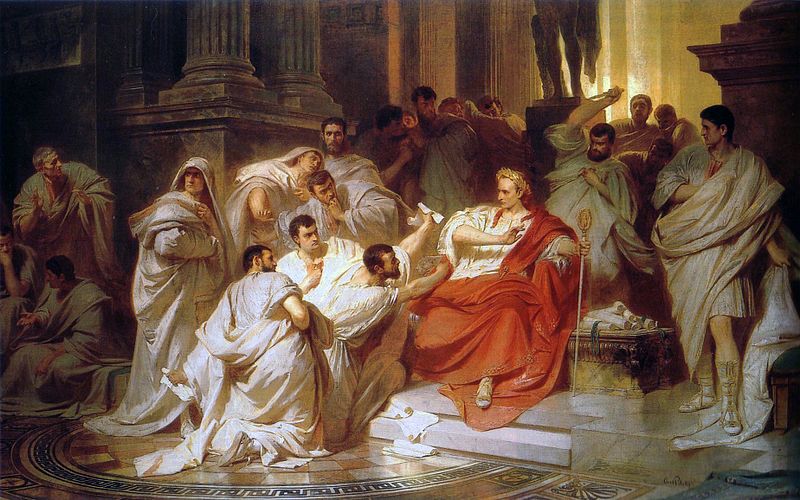

Caesar accepts the crown as dictator in perpetuity to the cheers of the populist masses. A group of Rome’s elite senators, wary of Caesar’s newfound power and politically ambitious themselves conspire to assassinate him.

By the time Caesar breathes his last gasp, “Et tu, Brute!” the play has only started to unfold the sequence of power struggles and bloody civil wars that marked the end of the Roman republic.

“Caesar is dead halfway through the play. It’s only a celebration of assassination if you leave then,” explained Andrew Hartley, chair of Shakespeare studies at University of North Carolina, Charlotte.

The negative reactions to the play have been largely overblown, he noted and mostly divided along party lines. “People see what they want to see and react accordingly.”

Hartley’s advice: “Watch the whole play.”

Hartley, who is currently working on a book about Julius Caesar in performance, explained that in the 20th and 21st centuries, Shakespeare’s classic tragedy has become “a politically very loaded play.”

In 2012, President Obama was featured in two different versions of Julius Caesar. In New York, the Acting Company put on a production at the Baruch Performing Arts Center set in Obama’s Washington, D.C. starring a characyter the audience was “unquestionably going to read” as President Obama.

The Guthrie and the Actors Theatre in Minneapolis put on their contemporary version of the play with Julius Caesar cast “as a tall, lanky black man.” The reviewer noted, “the Obama inference is a bit too obvious.”

The reason the 2012 productions didn’t cause the public outrage or pullout of corporate sponsors may be a reflection of the combustible political atmosphere around the new president.

The conspirator’s assassination of Caesar-Trump is certainly politically incendiary, as Shakespeare was in his day, but it does not rise to hate speech or incitement, Hartley advised.

“I understand that people are going to want to make these kinds of connections and point the finger at a sort of causal effect coming from the production,” he noted. “I don’t think to say that art generates violence makes sense. There is at least as much reflection as there is generation, probably more so.”

Critics of the play strongly disagree and see a worrying trend in the number of assassination threats against Trump, not only the apparently non-serious threats generated on social media that the Secret Service has to sort through, but celebrities openly toying with the idea in their performances.

Since Trump took office, a number of entertainers have depicted the assassination of the president or suggested violence against him.

In March, rapper Snoop Dogg performed a mock-execution of a clown-faced “Ronald Klump” in his music video for Lavender. Earlier this month, comedian Kathy Griffin held a fake severed head resembling Donald Trump in a photo shoot. She later apologized, saying the stunt “went too far.”

Gary Goldstein, author of ‘Reflections on the True Shakespeare’ as editor of the Elizabethan Review, explained that the Julius Caesar production follows in step with other events attempting to “abuse art and entertainment” to encourage violent political acts.

“It crosses a line by functioning as incitement,” he said, explaining that the recent portrayals of violence against Trump are “encouraging the deranged among us to take violent illegal action.”

Staging the play with depictions of current public officials is “encouraging the use of violence for nefarious ends,” Goldstein argued. “Everything else becomes secondary to the point you are trying to make at the pinnacle of the play, which is how in this historical instance a dictator was disposed of by the aristocrats of Rome.”

Keeping the works of the Bard relevant and attractive to new generations who already struggle with the language and distant historical settings is challenge for any art director. But even more challenging is trying to turn Shakespeare’s tragedy into a morality tale with heroes to emulate. Spoiler alert: the conspirators die in the end. Spoiler alert for the sequel: Marc Antony doesn’t make it either.

“Because we have become so unused to reading drama, we look for an authorial voice that tells us ‘here’s what the play means,’ and you never get that with Shakespeare,” Hartley emphasized. “The performance history of any play is a history of moving between different political positions and emphasizing different aspects of the play. That’s the way these things always are.”