The strict policy calls for immigration enforcement officers to refer 100 percent of illegal southwest border crossings to the Department of Justice for prosecution, a move that will result in the separation of families who try to enter the United States illegally, according to the department.

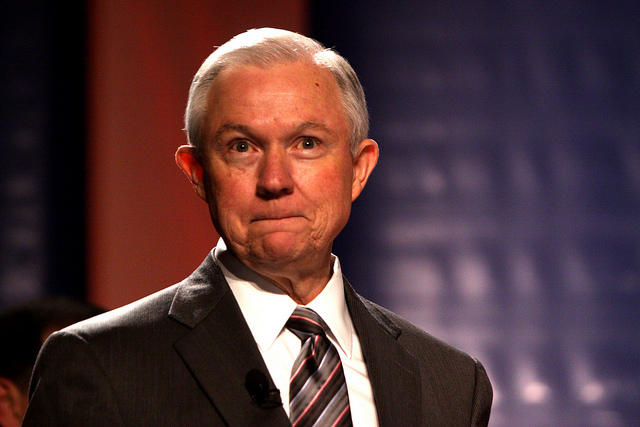

In a speech last week in Arizona, Attorney General Jeff Sessions stated that families trying to enter the country illegally will be impacted by the policy change. “If you are smuggling a child, then we will prosecute you and that child will be separated from you as required by law. If you don’t like that, then don’t smuggle children over our border,” Sessions said.

The policy reflects President Donald Trump’s efforts to strictly enforce existing immigration laws and was rolled out in a response to a dramatic year-on-year increase in illegal border crossings.

In April, U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) documented a 760 percent increase in the number of family units encountered at the border compared to the same time last year. Overall, the number of attempted illegal entries at the Southwest border was up more than 200 percent from 2017, when illegal entries hit a 46-year low.

The Department of Homeland Security reported the threat of family separations have proved effective an effective deterrent. CBP’s El Paso Sector launched an initiative in 2017 and saw a 64 percent decrease in illegal crossing when adults were prosecuted while putting their children at risk.

The outgoing director of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Thomas Homan denied the initiative represented “a blanket policy on separating families as a deterrent.” Homan told NBC News that separating families during criminal prosecutions is not new. “This has always been the policy,” he said. “But you will see more prosecutions because of the commitment to zero tolerance.”

In the past year, the number of prosecutions for illegal southwest border crossings reportedly doubled, according to Sessions who surged an additional 35 prosecutors and 18 immigration judges to the southwestern district last month in response to a migrant “caravan” from Central America. In recent weeks, prosecutors have brought charges against 11 members of the caravan, at least four of whom had children taken away from them, according to reports.

Under strict enforcement of U.S. law, individuals attempting to illegally cross the border are detained and sent to federal court for an often lengthy legal process. If they are traveling as a family, children are taken into the custody of Health and Human Services Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) and either placed with a relative or, if no relative can be found, put in foster care. In some cases, women and small children are kept together in family detention centers.

Immigration rights groups and lawmakers are challenging the Trump administration’s strict enforcement of the law, raising concerns that the immigration crackdown is tearing families apart and punishing legitimate asylum-seekers.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) sued the Trump administration and is seeking a nationwide injunction against the practice of separating families at the border. The suit was filed in March on behalf of two asylum-seekers who were separated from their children.

In Congress, a group of Democratic senators sent a letter to the DHS Inspector General calling for an investigation into whether the Trump administration is improperly separating families of asylum-seekers who arrive at the border. The letter was sent weeks before Attorney General Sessions announced the stricter policy.

Sen. Dick Durbin, D-Illinois, and 23 other Democrats denounced the policy of family separations, writing, “Any alleged deterrent effect this practice may have in reducing the number of individuals seeking safe haven under our laws is a wholly insufficient justification for forcibly separating children from their parents, particularly in light of its harmful impact.”

The senators demanded answers to basic questions, including how many children of asylum-seekers are currently detained separately from a parent and how many children of asylum-seekers have been separated from a parent since President Trump took office.

According to a January 2017 report to Congress by migrant and refugee support organizations, there is no government entity charged with systematically tracking family separations and no requirement that family separations be documented or justified.

Last month the New York Times reported at least 700 children have been taken from adults claiming to be their parents since October. That includes more than 100 children under the age of 4.

Joshua Breisblatt, a Senior Policy Analyst at the American Immigration Council, argued the separating minor children from their parents is “cruel and un-American.”

“Simply put, it is now government policy to separate families who cross the border—criminalizing the parents and sending their children to shelters and foster care,” Breisblatt stated. “This policy is punitive, impractical, and runs counter to our ideals.”

The latest change in enforcement policy may also increase the chance minors will be placed in foster care, rather than being reunited with their families, according to Kathryn Shepherd, the national advocacy counsel for the Immigration Justice Campaign. Under a proposed rule change, ICE will check the immigration status of relatives who come forward to claim children at the border. This will have a “chilling effect” on family members coming forward to sponsor minors seized at the border, she said.

With the Trump administration’s prioritizing all undocumented immigrants for deportation, Shepherd said family members “will be faced with the impossible choice of leaving their child in a shelter or foster care, or risking deportation by coming forward to reunite with him or her.”

A spokesperson with the Department of Homeland Security maintained its primary responsibility in dealing with families crossing the border is ensuring the welfare of children and separating families only when the child’s welfare is at risk or their custodian is legally detained.

Mark Krikorian, executive director of the Center for Immigration Studies, an organization that advocates for stricter immigration laws, argued the prosecution of illegal border crossings is less cruel than the alternative.

“People are being separated from their kids as a consequence of their committing the federal crime of crossing the border,” he said. “The alternative, of course, is anyone who brings a kid is automatically let go, which is what some anti-border people want. They want the presence of a child to be a ticket for any illegal alien into the United States.”

Krikorian said that approach was attempted under the previous administration and contributed to the sharp increase in the number of unaccompanied minors and families arriving illegally at the border. “That can’t be permitted. Otherwise, you have [networks] that start renting kids or people subjecting their own kids to the dangers of being smuggled,” he warned.

Since 2010, the number of unaccompanied children intercepted at the southwest border has more than doubled. Between March 2017 and March 2018, the number of unaccompanied children increased 800 percent, in what DHS Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen called a “troubling” trend.

Since October, DHS has made 30,000 prosecution referrals for illegal entry, up from 18,642 in 2017. The dramatic increase has put pressure on the U.S. immigration court system that was already facing systemic backlogs.

Despite surging additional Justice Department resources to the southwest border, the Trump administration’s crackdown on illegal border crossings has led to a continued expansion of the immigration court backlog, according to Human Rights First.

Since Trump took office and issued his first executive order on immigration, the backlog of immigration cases pending in U.S. courts has increased by more than 82,000, with the largest caseloads in Texas and California, according to the report. Human Rights First estimated the average wait time for a hearing is between three to five years.

Those numbers continue to increase, according to data gathered by the University of Syracuse, which reported a backlog of 680,000 immigration cases this year.

For children separated from their parents, that can mean long periods in foster care or in the custody of relatives in the United States, who may also be the targets of immigration enforcement if they are undocumented.

As both DHS and DOJ officials have predicted an increase in the number of prosecutions in response to the “zero-tolerance” policy, questions remain about managing the growing number of asylum cases and prosecutions for illegal border crossings.

The Trump administration has reportedly considered a plan to expedite judicial proceedings and deportations by imposing quotas and performance metrics on immigration judges. Last month, the Wall Street Journal reported on an internal DOJ memo outlining the standards including requiring to judges complete 700 cases per year and ensuring 85 percent of removal cases are completed within three days of a hearing on the merits of the case.