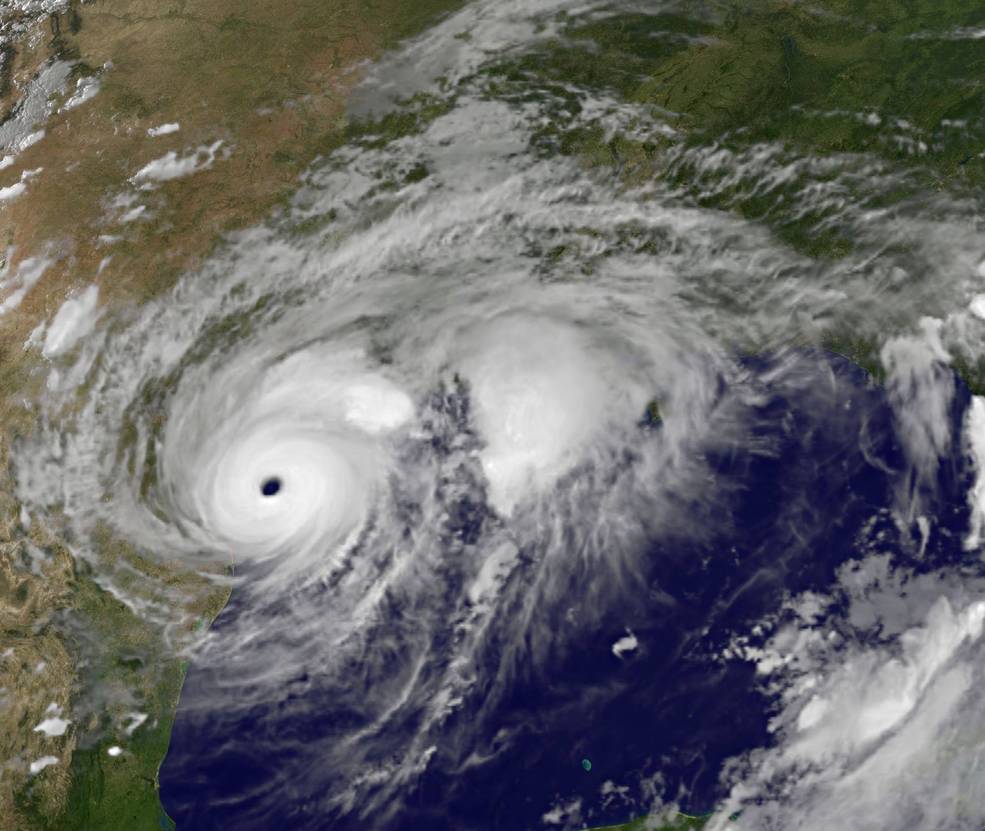

Monday, August 28th 2017 (WASHINGTON) Over the past week, people in Texas and around the country have been carefully tuned in to see the approach, development and aftermath of Hurricane Harvey, the first Category 4 hurricane to hit Texas in more than 50 years and possibly the worst flooding incident in a half-millenium.

Information about Harvey came in from space, the skies, the ocean and the ground. It was analyzed and disseminated as quickly as possible to make sure those in the pathway of the storm could be as prepared as possible.

On the front lines of that mission was the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). As the name would suggest, it’s the country’s eyes on the ocean and skies. Within NOAA, the National Hurricane Center was effectively the operational lead, coordinating the vast amount of data that goes into a hurricane forecast and making it available to emergency responders and the public at large.

In order to piece together the most accurate picture possible to save lives, NHC relies on a web of partners with truly stunning capabilities.

FROM SPACE:

From satellites and airborne assets to computer models and visualizations, NASA has an integral role in providing assistance to its partners, like NOAA and Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), who are responding to major weather events in real-time. Much of that assistance comes from sharing data and teaming up to operate new technology platforms.

“We are continuing on that quest to be more coordinated and more effective,” said Dalia Kirschbaum, hydrological

One of the most well-known support missions is the deployment of satellites, like the GOES-16, the newest generation geostationary weather satellite developed by NOAA and NASA and launched in November 2016.

More than a week before it made landfall in Texas, GOES-16 (also GOES-East) was already tracking Hurricane Harvey as a small tropical depression.

The stunning images of Harvey were taken from 22,300 miles above Earth by a satellite that is five-times the speed of NOAA’s older generation orbiters. The new generation GOES-16 is capable of producing a full, high-definition, multi-spectrum image of the continental U.S. every five minutes.

But the images are only one piece of the picture, Kirschbaum emphasized.

One of the challenges in tracking and forecasting hurricanes is getting below cloud cover, understanding how much energy and precipitation is caught up in a storm system.

By using synthetic aperture radar, scientists are able to send out a signal that can pierce through the clouds and return information about what lies just beneath the surface. Currently, the United States and India are working on a synthetic aperture radar, a satellite that can essentially look through the clouds

“One of the unique things we’ve been observing in Harvey is just the sheer amount of water,” Kirschbaum noted. For the first time, scientists at NASA, partnered with Japan’s Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) were able to map the precipitation in a storm like Harvey in 2 and 3-dimensions using the Global Precipitation Measurement Mission.

“This data helps give forecasters better clues about storm intensification and structure and movement,” she explained.

The visualization appeared regularly throughout the weekend showing the unusual dynamic of Hurricane Harvey that helped inform the emergency flood warnings.

Precipitation has been the defining characteristic of Hurricane Harvey. “The amount of rain that fell out of Harvey is actually not that unusual for hurricanes over open ocean,” Kirschbaum noted. What is different is that the storm was unable to proceed across land and disperse its energy store. It was essentially blocked by multiple pressure systems and locked in place over southeast Texas.

The latest addition to NASA’s suite of tropical storm monitoring suite is a cluster of eight micro-satellites, the Cyclone Global Navigation Satellite System (CYGNSS).

“The reason it’s cool is it observes active and reflective signals from GPS. Based on how the signals reflect off the ocean you can get a sense … of what is happening in the inner core of these specific storms, how they are moving and evolving.”

With CYGNSS, we can now measure the waves on the surface of the ocean, wind speed and that interaction between the ocean’s surface and the atmosphere, all from space.

Hurricane Harvey was the first major hurricane CYGNSS has observed since it was launched in January 2017. And while the information from Harvey has not yet been assessed, CYGNSS was definitely watching.

FROM THE AIR, ‘HURRICANE HUNTERS’:

The Air Force Reserve is not just one weekend per month to national service. For the 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron, defending the country means flying into the center of a storm. That includes everything from small tropical depressions to full-on Category 5 hurricanes.

Maj. Nicole Mitchell is a meteorologist with 53rd, better known as the Hurricane Hunters. On August 25, she was part of the crew that flew a suped-up C-130J cargo plane into Harvey before it made landfall.

“When we got in, it was being graded as a strong Cat. 2. Once we did our first pass we found the winds and pressure … justified the NHC to upgrade to a Cat. 3,” Mitchell said. “Once we finished flying and were headed for home it had continued to intensify to the point that it was a Category 4.”

Normally, the Hurricane Hunters will stay in the air for about 5 to 6 hours making X-shaped passes through the center of the storm. With each pass, the 6 to 8 member crew measures the size of the system, the pressure and even which side of the storm will be worse.

The plane itself is specially outfitted to collect weather data which is sent automatically to the NHC every ten minutes. The crew also releases dropsondes that collects information on pressure, dew point, and a full wind profile.

Also on board is a Stepped Frequency Microwave Radiometer (SFMR), a remote sensing instrument that reads microwave radiation coming off the ocean, indicating wind speed and direction.

“We call it a Smurf,” Mitchell laughed. “Even if there are clouds below us … this can read through the clouds and give us the surface windspeed. That’s very important because that’s what’s hitting the coastline.”

The job itself is incredible, Mitchell said, noting it requires a lot of math and science, “and hopefully you have a strong stomach.” Still, she recommends it to anyone who might be interested in joining the Air Force.

“You know that you’re making a difference, that the data is helping with the forecasts and the preparation and that you’re doing something that helps save lives,” she said.

NOAA also has its own fleet of hurricane hunting aircraft, including the WP-3D Orion and Gulfstream G-IV.

Like other trends in aviation, unmanned missions could be part of the future of NOAA’s future.

The Global Hawk is an unmanned aircraft shared between NASA and NOAA. In recent years, the Hurricane Research Division at NOAA has been experiementing with ways to use the UAV to gather real-time weather data and improve forecasting.

Though it did not fly into Harvey at the peak of the storm’s strength, the Global Hawk ran a reconnaissance mission to investigate the then-tropical cyclone on August 24.

One of the great advantages of the Global Hawk is it can fly for 30 hours straight at altitudes as high as 55,000 feet, perfect for Earth science missions.

ARE WE GETTING BETTER AT FORECASTING?

When it comes to the accuracy of forecasting these major storms, the more accurate the data, the better the prediction, the better chance to prepare.

According to the National Hurricane Center, all the coolest technology and monitoring capabilities have paid off in better lead time and more accurate forecasts.

Since Hurricane Andrew swept the southern Atlantic coast in 1992, National Hurricane Center has cut its forecasting errors by two-thirds on the size of storms that are approximately 3-days away.

The NHC has also extended its forecasts from three days in 1992 to five days, providing needed lead times for communities in the paths of these storms. Among its other proud accomplishments, the NHC has also expanded its presence on the web, giving more people access to forecasts.

Predicting the weather never has been an absolute science, but the improvements in monitoring and even modeling techniques have made a difference. Still, there is a long way to go to understanding the remarkable and volatile forces that are part of our experience here on Earth. cut its forecasting errors by two-thirds on storms that are approximately 3-days away.

Predicting the weather never has been an absolute science, but the improvements in monitoring and even modeling techniques have made a difference. Still, there is a long way to go to understanding the remarkable and volatile forces that are part of our experience here on Earth.