Monday, September 11th 2017 (WASHINGTON) – The 2017 hurricane season has already produced two record-shattering storms and the season is only halfway over.

So far there have been three major hurricanes, two of them made landfall on the U.S. Hurricane Harvey broke records for the continental U.S. by producing the single largest rainfall event in U.S. history, dumping 51.8 inches of rain on southeast Texas.

http://wpde.com/news/nation-

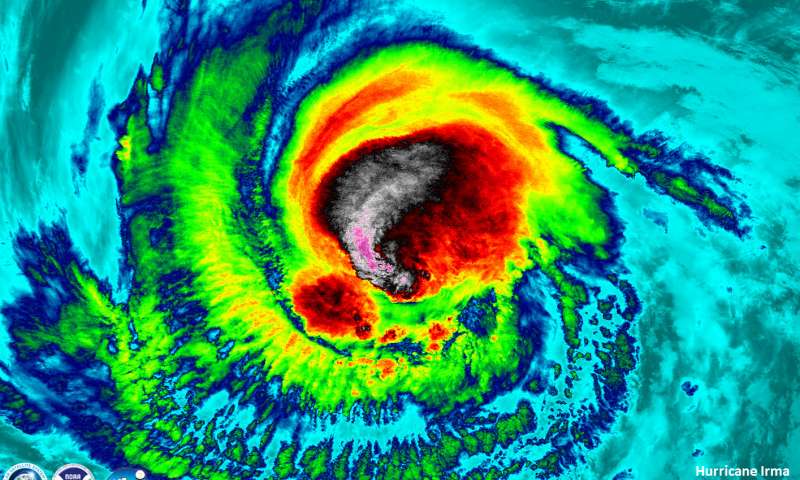

Hurricane Irma, not yet over, has already shattered a global record by maintaining maximum winds of 185 mph for 37 hours, the longest any cyclone has maintained that intensity.

It’s too soon to say how the 2017 hurricane season will stack up against previous years. Historically, the Atlantic hurricane season lasts from June 1 through November 30. But this season in the North Atlantic is already shaping up to be one of the busiest on record.

HOW TO COMPARE 2017 AGAINST PREVIOUS YEARS

There are a few ways to assess the intensity of a hurricane season. The first and simplest metric is to look at the total number of storms and the total number of major storms.

A more scientific measure is the total destructive force of the storms, a metric called the Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE). This unit measures the wind energy, strength and duration of a single storm and helps produce the sum total intensity of an entire season.strength and duration of a single storm and helps produce the sum total intensity of an entire season.

As of September 11, there are 11 named storms and 3 major storms, 2 of which made U.S. landfall. Historically, by this time there is an average of only 6.7 named storms and 12 named storms total per season.

In May, forecasters with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) predicted an above-normal season with a high likelihood of between 11 to 17 named storms and 2 to 4 major hurricanes.

By August, NOAA updated the forecast with even greater certainty predicting there could be as many as 19 named storms and 5 major hurricanes. In other words, Harvey and Irma may not be the last.

“The season has the potential to be extremely active, and could be the most active since 2010,” the administration said in its August press release. A season comparable to 2010, when there were 12 hurricanes and 19 named storms, could put 2017 on the board as the second busiest hurricane season on record.

“We are certainly poised to have a well-above normal season,” said Dr. Barry Keim, Louisiana state climatologist and professor at Louisiana State University. “The combination of warmer than normal sea surface temperatures and highly favorable upper air has just created the perfect environment to get these storms going.”

This year is already impressive in terms of midseason averages, according to the Colorado State University Tropical Meteorology Project, one of the more reliable forecasters in the country.

here have already been 44 days this season with a storm in the Atlantic, compared to the midseason average of 29 days.

The power of the storms has also been off the charts.

“These cyclones have expended more than twice the amount of energy of an average season at this juncture,” Keim explained.

Even before Irma has fully spun out all of her energy, the storm’s ACE hit 68 on Monday morning. That number in a single storm system is higher than the aggregated ACE in 18 storm systems on record since 1966.

Hurricane Ivan, the Category 5 storm that slammed the Caribbean and Florida in 2004, holds the top spot as the highest energy, longest duration hurricane in the North Atlantic with an ACE of 70.4.

THE MOST INTENSE HURRICANE SEASON ON RECORD

As busy and powerful as the 2017 Atlantic hurricane season has been, 2005 takes first place for the greatest number of hurricanes (15), the most Category 5 storms (Emily, Katrina, Rita and Wilma) and the highest accumulated cyclone energy on record (245).

That season also produced the costliest hurricane in U.S. history, Katrina, which slammed the Gulf Coast in late-August resulting in more than 1,200 fatalities and $108 billion in damage.

The only other year in recent history that compared to 2005 in terms of major hurricanes, was 1950 with a record number of 8 major storms and a total ACE of 243.

While 11 named storms is an impressive number, 2017 is lagging behind 2005 which had 15 named hurricanes by mid-season. Still, it is very difficult to predict how the next few months will play out.

“It’s tempting to go with a persistence forecast,” noted Dr. Gary Lackmann professor at North Carolina State University’s school of marine, earth and atmospheric sciences.

All the ingredients are there for a continued, intense storm season, from warm waters in cyclone breeding grounds to the absence of the El Niño climate effect, and light wind shear.

“It’s tempting to say, we’ll continue to have above normal activity like we did in some of the previous really active years just because conditions have been favorable up to this point and there’s no immediate sign that is going to change,” he added.

High-energy storm systems regularly leave a wake of cooler water in their path that could help take some of the fuel away from future storms. It is also possible that if the 2017 season produces another two or three major storms, as NOAA forecast, they could (hopefully) avoid making landfall.

WHY SO MANY STRONG HURRICANES?

“Something fundamentally changed in 1995,” Dr. Keim explained. At that time, sea surface temperatures started trending as warmer than normal, and that tracked with “hyperactive” hurricane seasons.

Of the most active hurricane seasons recorded since 1850, measured in terms of the total number of hurricanes, 11 of the top 15 took place after 1995.

Keim connected this increased intensity to the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation Index, which tracks multi-year trends in ocean surface temperatures.

“It’s not really understood what causes those oscillations,” he said, noting that there is simply not a long enough reliable data record. It is clear, however, that there is some kind of pattern. The most recent cool period lasted from around 1970 through 1994 sea surface temperatures tended to be cooler.

“The big question is how much longer are we going to stay in this warm phase with the sea surface temperatures,” Keim said. “An overriding question is if climate change is making it even worse.”

Keim suggested that he has not seen compelling evidence to support the conclusion that something has fundamentally changed the climate to create more hurricanes. What has emerged from recent climate models indicates that the number of tropical cyclones could stay the same or decrease, but the storms are likely to be more powerful.

Dr. Hans Paerl stressed the significance of not just the record-breaking storms of 2017, but the apparent increase in the number of extreme weather events.

“We need to look at this not just in terms of 2017,” he said, pointing to the record rainfalls and flooding associated with the last two decades of hyperactive hurricane seasons.

“We have had three 100 to 500-year storm events since 1999, the first one being here in North Carolina with Hurricane Floyd, then Matthew last year and now Harvey.” Matthew dropped over 20 inches of rain on North Carolina last year. Floyd shattered state records in South Carolina dumping 15 inches of rain in less than three days.

“That is really telling us something,” Paerl emphasized. “That is probably one of the most telltale signs that things have gotten more extreme.”

Despite the tendency to jump to conclusions about broader trends in the Earth’s climate from a single storm, hurricane and climate experts advise against it.

“It’s difficult to say for sure what will happen 100 years from now,” Lackmann said of the difficulties of climate science. “It’s hard enough to forecast seasonally.”

He is confident, however, that despite the challenges of hurricane science and understanding the climate at large, “there are a lot of good people working on it and doing their best to sort it out.”